Sectarian violence among Christians

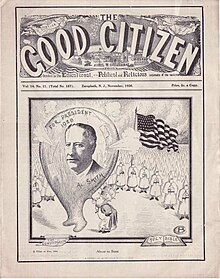

Sectarian violence among Christians is a recurring phenomenon, in which Christians engage in a form of communal violence known as sectarian violence. This form of violence can frequently be attributed to differences of religious beliefs between sects of Christianity (sectarianism). Sectarian violence among Christians was common, especially during late antiquity, and the years surrounding the protestant reformation, in which a German monk who was named Martin Luther disputed some of the Catholic Church's practices; particularly the doctrine of Indulgences, and it was crucial in the formation of a new sect of Christianity known as Protestantism.[1] During the latter half of the Renaissance was when sectarianism related violence was most common among Christians. Conflicts like the European wars of religion or Dutch Revolt ravaged Western Europe. In France there were the French Wars of Religion and in the United Kingdom anti-Catholic hate was heightened by the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. And while sectarian violence may seem like an archaic footnote today, sectarian violence among Christians still persists in the modern world with groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (which prominently uses the Bible along with the official KKK handbook, the Kloran, to espouse its teachings)[2] perpetuating violence among Catholics.[3]

The earliest period when widespread sectarian violence occurred among Christians was the period of late antiquity (3rd century CE to 8th century CE). Events like the wars which followed the Council of Chalcedon and Constantine's persecution of the Arians caused late antiquity to be considered one of the worst periods of time for a person to be a Christian in. Other conflicts such as the Albigensian Crusade, led to wars with over 1,000,000 casualties.[4]

Sectarian violence among Christians also became prominent during the Renaissance (from the 14th century to the 17th century CE) especially in Western Europe. In France, there were incidents of violence against a religious sect which was known as the Huguenots, whose members followed the teachings of the religious reformer John Calvin. These events included (but were not limited to) the Massacre of Vassy (which subsequently started the French Wars of Religion) and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. In Ireland some of the events that occurred during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland were so heinous, that they can be classified as war crimes.[5]

In the 19th-century US, anti-Catholic hate was salient due to the influx of Catholic immigrants who came to the US from Europe. At that time, the US was still in its infancy as a nation and it was dominated by white English speaking protestants, who traced back their ancestry to Northern Europe. So the disparity between the non-english speaking multiracial Catholics who came from various parts of Europe and the white nativist Protestant majority led to discrimination against the former by the latter.[3]

Late antiquity

[edit]Andrew Stephenson describes late antiquity as "one of the darkest periods in the history of Christianity" characterizing it as mingling the evils of "worldly ambition, false philosophy, sectarian violence and riotous living."[6] Constantine initially persecuted the Arians but eventually ceased the persecution and declared himself a convert to their theology. Sectarian violence became more frequent and more intense during the reign of Constantius II. When Paul, the orthodox bishop of Constantinople, was banished by imperial decree, a riot broke out that resulted in 3000 deaths. Paul was deposed five times before finally being strangled by imperial decree. Monks in Alexandria were the first to gain a reputation for violence and cruelty. Although less frequent than in Antioch and Constantinople, sectarian disturbances also racked Antioch. At Ephesus, a fight broke out in a council of bishops resulting in one of them being murdered. Gibbon's assessment was that "the bonds of civil society were torn asunder by the fury of religious factions." Gregory of Nazianzus lamented that the Kingdom of heaven had been converted into the "image of hell" by religious discord.[7]

Athanasius of Alexandria

[edit]

There are at present two completely opposite views about the personality of Athanasius. While some scholars praise him as an orthodox saint with great character, others see him as a power-hungry politician who employed questionable ecclesiastical tactics. Richard Rubenstein and Timothy Barnes have painted a less than flattering picture of the saint. One of the allegations against him involves suppression of dissent through violence and murder.[8][9]

Arianism

[edit]Following the abortive effort by Julian the Apostate to restore paganism in the empire, the emperor Valens—himself an Arian—renewed the persecution of Nicene hierarchs. However, Valen's successor Theodosius I effectively wiped out Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, which condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed.[10] This generally ended the influence of Arianism among the non-Germanic peoples of the Roman Empire.

Circumcellions

[edit]The Circumcellions were fanatical bands of predatory peasants that flourished in North Africa in the 4th century.[11] At first they were concerned with remedying social grievances, but they became linked with the Donatist sect.[11] They condemned property and slavery, and advocated canceling debts and freeing slaves.[12]

Donatists prized martyrdom and had a special devotion for the martyrs, rendering honours to their graves. The Circumcellions had come to regard martyrdom as the true Christian virtue, and thus disagreed with the Episcopal see of Carthage on the primacy of chastity, sobriety, humility, and charity. Instead, they focused on bringing about their own martyrdom—by any means possible. They survived until the fourth century in Africa, when their desire for martyrdom was fulfilled due to persecution.

Council of Chalcedon

[edit]In 451, Pope Leo I urged Anatolius to convene an ecumenical council to set aside the 449 Second Council of Ephesus, better known as the "Robber Council". The Council of Chalcedon was highly influential and marked a key turning point in the Christological debates that broke apart the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries.[13] Severus of Antioch is said to have stirred up a fierce religious war among the population of Alexandria, resulting in bloodshed and conflagrations (Labbe, v. 121). To escape punishment for this violence, he fled to Constantinople, supported by a band of two hundred Non-Chalcedonian monks. Anastasius, who succeeded Zeno as emperor in 491, was a professed Non-Chalcedonian, and received Severus with honor. His presence initiated a period of fighting in Constantinople between rival bands of monks, Chalcedonian and Non, which ended in AD 511 with the humiliation of Anastasius, the temporary triumph of the patriarch Macedonius II, and the reversal of the Non-Chalcedonian cause (Theophanes, p. 132). At the Council of Constantinople in 518, Syrian monks placed the responsibility for the slaughter of 350 Chalcedonian monks and the appropriation of church vessels on Severus' shoulders.[14] The associated theological disputes, political rivalry, and sectarian violence produced a schism that persists to this day between Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian churches.

France

[edit]Albigensian Crusade

[edit]Jonathan Barker cited the Albigensian Crusade, launched by Pope Innocent III against followers of Catharism, as an example of Christian state terrorism.[15] The 20-year war led to an estimated one million casualties.[4] The Cathar teachings rejected the principles of material wealth and power as being in direct conflict with the principle of love. They worshiped in private houses rather than churches, without the sacraments or the cross, which they rejected as part of the world of matter, and sexual intercourse was considered sinful, but in other respects they followed conventional teachings, reciting the Lord's prayer and reading from Biblical scriptures.[4] They believed that the Saviour was a "heavenly being merely masquerading as human to bring salvation to the elect, who often have to conceal themselves from the world, and who are set apart by their special knowledge and personal purity".[4]

Cathars rejected the Old Testament and its God, whom they named Rex Mundi (Latin for "king of the world"), whom they saw as a blind usurper who demanded fearful obedience and worship and who, under the most false pretexts, tormented and murdered those whom he called "his children" They proclaimed that there was a higher God—the True God—and Jesus was his messenger. They held that the physical world was evil and created by Rex Mundi, who encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful; the second god, the one whom they worshipped, was entirely disincarnate: a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter – He was the god of love, order and peace.[16] According to Barker, the Albigenses had developed a culture that "fostered tolerance of Jews and Muslims, respect for women and women priests, the appreciation of poetry, music and beauty, [had it] been allowed to survive and thrive, it is possible the Europe might have been spared its wars of religion, its witch-hunts and its holocausts of victims sacrificed in later centuries to religious and ideological bigotry".[15]: 74 When asked by his followers how to differentiate between heretics and the ordinary public, Abbe Arnaud Amalric, head of the Cistercian monastic order, simply said "Kill them all, God will recognize his own!".[4]

Catholic–Protestant

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (December 2010) |

Historically, the past governments of some Catholic countries once persecuted Protestants as heretics. For example, the substantial Protestant population of France (the Huguenots) was expelled from the kingdom in the 1680s following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In Spain, the Inquisition sought to root out not only Protestantism but also crypto-Jews and crypto-Muslims (moriscos); elsewhere the Papal Inquisition held similar goals. In most places where Protestantism is the majority or "official" religion, there have been examples of Catholics being persecuted.[citation needed] In countries where the Reformation was successful, this often lay in the perception that Catholics retained allegiance to a 'foreign' power (the Papacy), causing them to be regarded with suspicion. Sometimes this mistrust manifested itself in Catholics being subjected to restrictions and discrimination, which itself led to further conflict. For example, before Catholic Emancipation in 1829, Catholics were forbidden from voting, becoming MPs or buying land in Ireland.

As of 2010[update], bigotry and discrimination in employment are usually restricted to a few places where extreme forms of religion[clarification needed] are the norm, or in areas with a long history of sectarian violence and tension, such as Northern Ireland (especially in terms of employment; however, this is dying out in this jurisdiction, thanks to strictly-enforced legislation. Reverse discrimination now takes place in terms of employment quotas which are now applied). In places where more "moderate" forms of Protestantism (such as Anglicanism or Episcopalianism) prevail, the two traditions do not become polarized against each other, and usually co-exist peacefully. Especially in England, sectarianism is nowadays almost unheard of. However, in Western Scotland (where Calvinism and Presbyterianism are the norm) sectarian divisions can still sometimes arise between Catholics and Protestants. In the early years following the Scottish Reformation there was internal sectarian tension between Church of Scotland Presbyterians and 'High Church' Anglicans, the former regarding the latter as having retained too many attitudes and practices from the pre-Reformation Catholic era.

European wars of religion

[edit]

Following the onset of the Protestant Reformation, a series of wars were waged in Europe starting circa 1524 and continuing intermittently until 1648. Although sometimes unconnected, all of these wars were strongly influenced by the religious change of the period, and the conflict and rivalry that it produced. According to Miroslav Volf, the European wars of religion were a major factor behind the "emergence of secularizing modernity".

Netherlands

[edit]The Low Countries have a particular history of religious conflict which had its roots in the Calvinist reformation movement of the 1560s. These conflicts became known as the Dutch Revolt or the Eighty Years' War. By dynastic inheritance, the whole of the Netherlands (including present day Belgium) had come to be ruled by the kings of Spain. Following aggressive Calvinist preaching in and around the rich merchant cities of the southern Netherlands, organized anti-Catholic religious protests grew in violence and frequency. Repression by the Catholic Spaniards in response caused Dutch Calvinists to rebel, sparking devades of war until the Dutch Republic won its independence from Spain.

France

[edit]The French Wars of Religion (1562–98) is the name given to a period of civil infighting and military operations, primarily fought between French Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots). The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and House of Guise (Lorraine), and both sides received assistance from foreign sources.[17]

The Massacre of Vassy in 1562 is generally considered to be the beginning of the Wars of Religion and the Edict of Nantes at least ended this series of conflicts. During this time, complex diplomatic negotiations and agreements of peace were followed by renewed conflict and power struggles.[citation needed]

At the conclusion of the conflict in 1598, Huguenots were granted substantial rights and freedoms by the Edict of Nantes, though it did not end hostility towards them. The wars weakened the authority of the monarchy, already fragile under the rule of Francis II and then Charles IX, though it later reaffirmed its role under Henry IV.[18]

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations, followed by a wave of Roman Catholic mob violence, both directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants), during the French Wars of Religion. The massacre began two days after the attempted assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots. Starting on 23 August 1572 (the eve of the feast of Bartholomew the Apostle) with murders on orders of the king of a group of Huguenot leaders including Coligny, the massacres spread throughout Paris. Lasting several weeks, the massacre extended to other urban centres and the countryside. Modern estimates for the number of dead vary widely between 5,000 and 30,000 in total.

The massacre also marked a turning point in the French Wars of Religion. The Huguenot political movement was crippled by the loss of many of its prominent aristocratic leaders, as well as many re-conversions by the rank and file, and those who remained were increasingly radicalized. Though by no means unique, it "was the worst of the century's religious massacres."[19] Throughout Europe, it "printed on Protestant minds the indelible conviction that Catholicism was a bloody and treacherous religion".[20]

Pope Gregory XIII sent the leader of the massacres a Golden Rose, and said that the massacres "gave him more pleasure than fifty Battles of Lepanto, and he commissioned Vasari to paint frescoes of it in the Vatican".[21] The killings have been called "the worst of the century's religious massacres",[19] and led to the start of the fourth war of the French Wars of Religion.

Ireland

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (July 2010) |

Since the 16th century there has been sectarian conflict of varying intensity between Roman Catholics and Protestants in Ireland. This religious sectarianism is connected to a degree with nationalism. Northern Ireland has seen inter-communal conflict for more than four centuries and there are records of religious ministers or clerics, the agents for absentee landlords, aspiring politicians, and members of the landed gentry stirring up and capitalizing on sectarian hatred and violence as far back as the late 18th century (See 'Two Hundred Years in the Citadel')Inside the Orange Citadel

This has been particularly intense in Northern Ireland since the 17th century. There are records of religious ministers or clerics, politicians, and members of the landed gentry stirring up and capitalizing on sectarian hatred and violence as far back as the late 18th century.[citation needed]

William Edward Hartpole Lecky, an Irish historian, wrote "If the characteristic mark of a healthy Christianity be to unite its members by a bond of fraternity and love, then there is no country where Christianity has more completely failed than Ireland".[22]

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, 1649–53

[edit]Lutz and Lutz cited the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland as terrorism; "The draconian laws applied by Oliver Cromwell in Ireland were an early version of ethnic cleansing. The Catholic Irish were to be expelled to the northwestern areas of the island. Relocation rather than extermination was the goal."[23] Daniel Chirot has argued that genocide was originally the goal, inspired by the Biblical account of Joshua and the genocide following the Battle of Jericho:[24]: 3

Northern Ireland

[edit]Steve Bruce, a sociologist, wrote "The Northern Ireland conflict is a religious conflict. Economic and social considerations are also crucial, but it was the fact that the competing populations in Ireland adhered and still adhere to competing religious traditions which has given the conflict its enduring and intractable quality".[25]: 249 Reviewers agreed "Of course the Northern Ireland conflict is at heart religious".[26]

John Hickey wrote "Politics in the North is not politics exploiting religion. That is far too simple an explanation: it is one which trips readily off the tongue of commentators who are used to a cultural style in which the politically pragmatic is the normal way of conducting affairs and all other considerations are put to its use. In the case of Northern Ireland the relationship is much more complex. It is more a question of religion inspiring politics than of politics making use of religion. It is a situation more akin to the first half of seventeenth‑century England than to the last quarter of twentieth century Britain".[27]

The period from 1969 to 2002 is known as "The Troubles". Nearly all the people living in Northern Ireland identified themselves as belonging to either the Protestant or the Catholic community. People of no religion and non-Christian faiths are still considered as belonging to one of the two "sects" along with churchgoers. In this context, "Protestants" means essentially descendants of immigrants from Scotland and England settled in Ulster during or soon after the 1690s; also known as "Loyalists" or "Unionist" because they generally support politically the status of Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom. "Catholics" means descendants of the pre-1690 indigenous Irish population; also known as "Nationalist" and "Republicans"; who generally politically favour a united Ireland.

Reactions to sectarian domination and abuse have resulted in accusations of sectarianism being levelled against the minority community. It has been argued, however, that those reactions would be better understood in terms of a struggle against the sectarianism that governs relations between the two communities and which has resulted in the denial of human rights to the minority community.[28]

There are organizations dedicated to the reduction of sectarianism in Northern Ireland. The Corrymeela Community of Ballycastle operates a retreat centre on the northern coast of Northern Ireland to bring Catholics and Protestants together to discuss their differences and similarities. The Ulster Project works with teenagers from Northern Ireland and the United States to provide safe, non-denominational environments to discuss sectarianism in Northern Ireland. These organizations are attempting to bridge the gap of historical prejudice between the two religious communities.

Northern Ireland has introduced a Private Day of Reflection,[29] since 2007, to mark the transition to a post-[sectarian] conflict society, an initiative of the cross-community Healing through Remembering[30] organisation and research project.

United Kingdom

[edit]

The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More and John Fisher were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

The Act of Supremacy (which asserted England's independence from papal authority) was repealed in 1554 by Henry's daughter Queen Mary I (who was a devout Catholic) when she reinstated Catholicism as England's state religion. Another Act of Supremacy was passed in 1559 under Elizabeth I, along with an Act of Uniformity which made worship in the Church of England compulsory. Anyone who took office in the English church or government was required to take the Oath of Supremacy; penalties for violating it included hanging and quartering. Attendance at Anglican services became obligatory—those who refused to attend Anglican services, whether Roman Catholics or Puritans, were fined and physically punished as recusants.

In the time of Elizabeth I, the persecution of the adherents of the Reformed religion, both Anglican and Nonconformist Protestants alike, which had occurred during the reign of her elder half-sister Queen Mary I, was used to fuel strong anti-Catholic propaganda in the hugely influential Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Those who had died in Mary's reign, under the Marian Persecutions, were effectively canonised by this work of hagiography. In 1571 the Convocation of the Church of England ordered that copies of the Book of Martyrs should be kept for public inspection in all cathedrals and in the houses of church dignitaries. The book was also displayed in many Anglican parish churches alongside the Holy Bible. The passionate intensity of its style and its vivid and picturesque dialogues made the book very popular among Puritan and Low Church families, Anglican and nonconformist Protestant, down to the nineteenth century. In a period of extreme partisanship on all sides of the religious debate, the exaggeratedly partisan church history of the earlier portion of the book, with its grotesque stories of popes and monks, contributed to fuel anti-Catholic prejudices in England, as did the story of the sufferings of several hundred Reformers (both Anglican and Nonconformist Protestant) who had been burnt at the stake under Mary and Bishop Bonner.

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power in the country; this was seemingly confirmed by various actions by the Vatican. In 1570, Pope Pius V sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once.

Elizabeth's persecution of Catholic Jesuit missionaries led to the executions of many priests such as Edmund Campion. Although at the time of their deaths, they were considered traitors to England, they are now considered martyrs by the Catholic Church.

Later several accusations fueled strong anti-Catholicism in England, including the Gunpowder Plot, in which Guy Fawkes and other Catholic conspirators where accused of planning to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session.

Glasgow, Scotland

[edit]Sectarianism in Glasgow takes the form of religious and political sectarian rivalry between Roman Catholics and Protestants. It is reinforced by the Old Firm rivalry between the football clubs: Rangers F.C. and Celtic F.C.[31] Members of the public appear divided on the strength of the relationship between football and sectarianism.[31]

United States

[edit]Anti-Catholicism

[edit]Anti-Catholicism reached a peak in the mid nineteenth century when Protestant leaders became alarmed by the heavy influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Some of them believed that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon who is mentioned in the Book of Revelation.[32]

In the 1830s and 1840s, prominent Protestant leaders, such as Lyman Beecher and Horace Bushnell, attacked the Catholic Church as not only theologically unsound but an enemy of republican values.[33] Some scholars view the anti-Catholic rhetoric of Beecher and Bushnell as having contributed to anti-Irish and anti-Catholic mob violence.[34]

Beecher's well-known "Plea for the West" (1835) urged Protestants to exclude Catholics from western settlements. The Catholic Church's official silence on the subject of slavery also garnered the enmity of northern Protestants. Intolerance became more than an attitude on 11 August 1834, when a mob set fire to an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.[35] This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for spreading violence and drunkness.[36] In the late nineteenth century southern United States evangelical Protestants used a wide range of terror activities, including lynching, murder, attempted murder, rape, beating, tar-and-feathering, whipping, and destruction of property, to suppress competition from black Christians (who saw Christ as the saviour of the black oppressed), Mormons, Native Americans, foreign-born immigrants, Jews, and Catholics.[37]

Anti-Mormonism

[edit]Early Mormon history is marred by many instances of violent persecution, which have shaped the faith's attitudes towards violence. The first significant act of violent persecution occurred in Missouri. the Mormons who lived there tended to vote as a bloc, which caused them to wield "considerable political and economic influence," and as a result, they often unseated local political leaders and earned long-lasting enmity in frontier communities.[38] These differences culminated in the Missouri Mormon War and the eventual issuing of an executive order (since called the extermination order within the LDS community) by Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs, which declared that "the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State." Three days later, a renegade militia unit attacked a Mormon settlement at Haun's Mill. After the initial attack, several of those who had been wounded or had surrendered were shot dead, and Justice of Peace Thomas McBride was hacked to death by a corn scythe. As a result of the massacre, 18 Mormons were murdered, 15 more were injured, and the property of most of those who remained alive was stolen and they were left destitute as a result; none of the militiamen were killed. The expulsion of several thousand Mormons from Missouri occurred during the winter, which heightened the problems for many of the refugees, who lacked food, shelter, and adequate medicine.[39] The extermination order was not formally rescinded until 25 June 1976.[40]

In Nauvoo, Illinois, persecutions were often based on the alleged tendency of Mormons to "dominate community, economic, and political life wherever they landed."[41] The city of Nauvoo had become the largest city in Illinois, it even rivaled Chicago in size, the city council was predominantly Mormon, and the Nauvoo Legion (the Mormon militia) continued to grow. Other issues of contention included plural marriage, freedom of speech, the anti-slavery views which Smith expressed during his 1844 presidential campaign, and Smith's teachings on the deification of man. After the destruction of the press of the Nauvoo Expositor, Smith was arrested and incarcerated in the Carthage Jail where he and his brother Hyrum were killed by a mob on 27 June 1844. The persecution in Illinois became so severe that most of the residents of Nauvoo fled across the Mississippi River in February 1846. Following the flight of the Mormons from Illinois, mobs poured in and desecrated the Nauvoo Temple. For a short period of time, the Mormons were forced to establish refugee camps in the plains of Iowa and Nebraska, before pushing further West to the Great Basin in an attempt to completely escape the violence. An estimated 1 in 12 people died in these camps during the first year.[42]

Even after the Mormons established a community hundreds of miles away in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, anti-Mormon activists in the Utah Territory convinced U.S. President James Buchanan that the Mormons in the territory were rebelling against the United States; critics pointed to the Mountain Meadows massacre and plural marriage as signs of the rebellion. In response, President Buchanan sent one-third of the American standing army in 1857 to Utah in what is known as the Utah War.

The Mountain Meadows massacre of 7–11 September 1857 was widely blamed on the church's teaching of blood atonement and the anti-United States rhetoric which was espoused by LDS Church leaders during the Utah War.[citation needed] The widely publicized massacre was a mass killing of Arkansan emigrants by a Mormon militia and Paiute Indian recruits, led by John D. Lee, who was later executed for his role in the killings. Though widely connected with the blood atonement doctrine by the United States press and general public, there is no direct evidence that the massacre was related to "saving" the emigrants by the shedding of their blood (as they had not entered into Mormon covenants); rather, most commentators view it as an act of intended retribution, acted upon due to rumors that some members of this party were intending on joining with American troops in attacking the Mormons. Young was accused of either directing the massacre, or with complicity after the fact. However, when Brigham Young was interviewed on the matter and asked if he believed in blood atonement, he replied, "I do, and I believe that Lee has not half atoned for his great crime." He said "we believe that execution should be done by the shedding of blood instead of by hanging," but only "according to the laws of the land."[43]: 242

20th century

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Roman Catholic.[44] Anti-Catholicism was widespread in the 1920s; anti-Catholics, including the Ku Klux Klan, believed that Catholicism was incompatible with democracy and that parochial schools encouraged separatism and kept Catholics from becoming loyal Americans. The Catholics responded to such prejudices by repeatedly asserting their rights as American citizens and by arguing that they, not the nativists (anti-Catholics), were true patriots since they believed in the right to freedom of religion.[45]

With the rise of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the 1920s, anti-Catholic rhetoric intensified. The Catholic Church of the Little Flower was first built in 1925 in Royal Oak, Michigan, a largely Protestant area. Two weeks after it opened, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of the church.[46]

Canada

[edit]The Harbour Grace Affray was an armed conflict of religious violence that happened on Saint Stephen's Day, 1883 in the town of Harbour Grace, Colony of Newfoundland, now modern day Canada, between members of the Loyal Orange Association and the Roman Catholics.[47]

Australia

[edit]Sectarianism in Australia is a historical legacy from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Catholic-Eastern Orthodox

[edit]Crusades

[edit]Although the First Crusade was initially launched in response to Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos's appeal for help in repelling the invading Seljuq Turks from Anatolia, one of the lasting legacies of the Crusades would "further separate the Eastern and Western branches of Christianity from each other."[48]

The Massacre of the Latins occurred in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in 1182. It was a large-scale massacre of the "Latin" (Roman Catholic) merchants and their families, who at that time dominated the city's maritime trade and financial sector. Although precise numbers are unavailable, the bulk of the Latin community, estimated at over 60,000 at the time,[49] was wiped out or forced to flee. The Genoese and Pisan communities were especially decimated, and some 4,000 survivors were sold to the Turks as slaves.[50]

The Siege of Constantinople (also called the Fourth Crusade) occurred in 1204; it destroyed parts of the capital of the Byzantine Empire as it was captured by Western European and Venetian Crusaders. After the fall, the Crusaders inflicted a savage sacking on the city[51] for three days, during which many ancient and medieval Roman and Greek works were either stolen or destroyed. Despite their oaths and the threat of excommunication, the Crusaders systematically desecrated the city's holy sanctuaries by either destroying or stealing whatever they could lay their hands on; nothing was spared.

Yugoslav wars

[edit]The Yugoslav wars are sometimes labelled religious/sectarian conflicts, which is disputed by academia. They were primarily interethnic wars which were waged between several states which seceded from Yugoslavia prior to the wars. The Croats and the Slovenes have traditionally been Catholic, the Serbs, the Montenegrins and the Macedonians have traditionally been Eastern Orthodox, and the Bosniaks and most Albanians have traditionally been Sunni Muslim. Although the conflicts were not caused by religious differences, to some degree, religious affiliations served as markers of group identity during their durations, despite the relatively low rates of religious practice and belief among these various groups as a result of decades of communist rule in the formally secular and irreligious Yugoslavia.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gundacker, Jay (8 August 2021). "Historical Context for The Protestant Reformation". www.college.columbia.edu.

- ^ Johnson, Daryl (25 September 2017). "Hate In God's Name". www.splcenter.org.

- ^ a b Zeitz, Josh (23 September 2015). "When America Hated Catholics". www.politico.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Massacre of the Pure". TIME Magazine. 28 April 1961. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008.

- ^ Mulraney, Francis (11 September 2020). "Oliver Cromwell's war crimes, the Massacre of Drogheda in 1649". www.irishcentral.com. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Stephenson, Andrew (1919). The history of Christianity from the origin of Christianity to the time of Gregory the Great, Volume 2. R. G. Badger. p. 186.

Sectarian violence Nestorianism.

- ^ Harte, Bret (1892). Overland monthly, and Out west magazine, Volume 20. Samuel Carson. p. 254.

- ^ Barnes, Timothy D., Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993),37

- ^ Rubenstein,106

- ^ See Vasiliev, A.,"The Church and the State at the End of the Fourth Century", from History of the Byzantine Empire, Chapter One. Retrieved on 2 February 2010. The text of this version of the Nicene Creed

- ^ a b "Circumcellions." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Durant, Will (1972). The age of faith. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- ^ The acts of the Council of Chalcedon by Council of Chalcedon, Richard Price, Michael Gaddis 2006 ISBN 0-85323-039-0, pages 1–5 [1]

- ^ Menze, Volker-Lorenz (2008). Justinian and the making of the Syrian Orthodox Church. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Jonathan Barker (2003). The no-nonsense guide to terrorism. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-433-2.

- ^ See Catharism and Catharism#Theology

- ^ Knecht, Robert Jean (2002). The French Religious War 1562–1598: essential histories. Bloomsbury. p. 96. ISBN 9781841763958.

- ^ "The French Wars of Religion | Western Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b H.G. Koenigsberger, George L.Mosse, G.Q. Bowler, "Europe in the Sixteenth Century", Second Edition, Longman, 1989

- ^ Chadwick, H. & Evans, G.R. (1987), Atlas of the Christian Church, Macmillan, London, ISBN 0-333-44157-5 hardback, pp. 113;

- ^ Ian Gilmour; Andrew Gilmour (1988). "Terrorism review". Journal of Palestine Studies. 17 (2). University of California Press: 136. doi:10.1525/jps.1988.17.3.00p0024k.

- ^ William Edward Hartpole Lecky (1892). A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century.

- ^ Lutz,James M and Lutz, Brenda J (2004). Global Terrorism. Routledge. p. 193. ISBN 0-415-70051-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daniel Chirot. Why Some Wars Become Genocidal and Others Don't (PDF). Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2008.

- ^ Steve Bruce (1986). God Save Ulster. Oxford University Press. p. 249. ISBN 0-19-285217-5.

- ^ David Harkness (October 1989). "God Save Ulster: The Religion and Politics of Paisleyism by Steve Bruce (review)". The English Historical Review. 104 (413). Oxford University Press.

- ^ John Hickey (1984). Religion and the Northern Ireland Problem. Gill and Macmillan. p. 67. ISBN 0-7171-1115-6.

- ^ "Inside the Orange Citadel". orangecitadel.blogspot.com.

- ^ "Day of Reflection : Ireland".

- ^ "Healing Through Remembering – Healing Through Remembering". 24 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Sectarianism in Glasgow" (PDF). Glasgow City Council. January 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2005. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D. (1986). Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-8386-3227-0.

- ^ Beecher, Lyman (1835). A Plea for the West. Cincinnati: Truman & Smith. p. 61. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

The Catholic system is adverse to liberty, and the clergy to a great extent are dependent on foreigners opposed to the principles of our government, for patronage and support.

- ^ Matthews, Terry. "Lecture 16 – Catholicism in Nineteenth Century America". Archived from the original on 29 May 2001. Retrieved 3 April 2009.Stravinskas, Peter, M.J., Shaw, Russell (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87973-669-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jimmy Akin (1 March 2001). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Hennesey, James J. (1983). American Catholics. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-19-503268-0.

- ^ Patrick Q. Mason (6 July 2005). Sinners in the Hands of an Angry Mob: Violence against Religious Outsiders in the U.S. South, 1865–1910 (PDF). University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ Monroe, R.D. "Congress and the Mexican War, 1844–1849". lincoln.lib.niu.edu. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- ^ William G. Hartley, "The Saints’ Forced Exodus from Missouri," in Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson, eds., Joseph Smith: The Prophet and Seer, 347–89.

- ^ Bond, Christopher S. (25 June 1976). "Executive Order Number 44" (PDF). State of Missouri, Executive Office.

- ^ VandeCreek, Drew E. "Religion and Culture". lincoln.lib.niu.edu. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- ^ Richard E. Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 1846–1852: "And Should We Die …" (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 141.

- ^ Young, Brigham (30 April 1877), "Interview with Brigham Young", Deseret News, vol. 26, no. 16 (published 23 May 1877), pp. 242–43, archived from the original on 2 September 2012

- ^ "History of the Catholic Church in the United States | USCCB". www.usccb.org. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Dumenil (1991)

- ^ Shannon, William V. (1989) [1963]. The American Irish: a political and social portrait. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-87023-689-1. OCLC 19670135.

Ku Klux Klan shrine of the little flower.

- ^ Dohey, Larry (25 December 2017). "The Harbour Grace Affray".

- ^ Bellinger, Charles K. (2001). The genealogy of violence: reflections on creation, freedom, and evil. Oxford University Press US. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-803084-3.

- ^ The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 950–1250. Cambridge University Press. 1986. pp. 506–508. ISBN 978-0-521-26645-1.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-521-42894-1.

- ^ "Sack of Constantinople, 1204". Agiasofia.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

Further reading

[edit]- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- McTernan, Oliver J. 2003. Violence in God's name: religion in an age of conflict. Orbis Books.